Inflation is due to demand exceeding supply at current prices as well as increases in the cost of supplying goods and services. The supply of services is determined in large part by changes in labor productivity, the supply of labor and the efficiency of the allocation of resources. The cost of services is determined largely by wages. There are also different multiplier effects from consumption of different goods. For instance, consumption of domestically produced services puts spending power into the hands of U.S. workers and to a lesser extent U.S. firms. Consumption of imported goods puts spending power into the hands of foreign workers and foreign firms. U.S. workers and firms are more likely to spend their income on U.S. produced goods and services than are foreign workers. On the cost side, wages are the main determinant of the cost of services. Increased labor demand and decreased labor participation rates push up wages and thus the cost of providing services, which is then reflected in the prices of services. Changes in the composition of the labor force can also affect labor productivity. If less productive workers are being hired, then reported changes in average wages will understate the increased cost of providing services.1 The cost of providing goods and services is also affected by changes in total factor productivity: the productivity of both labor and capital. Total factor productivity (both with and without adjustments for utilization) as measured by the San Francisco Fed has declined in the last three quarters. This is likely due to changes in the composition of the labor force.

To get to the punchline, I think most of the commentary I’ve read overestimates the risk of recession in the near term. I think the risk of recession is low and the disinflationary effects of falls in commodity prices and a strong dollar will dissipate over the course of the next year. Thus the risk of continued inflation is high. If I’m correct, interest rates will be higher for longer than markets are predicting.

Labor Market Demand

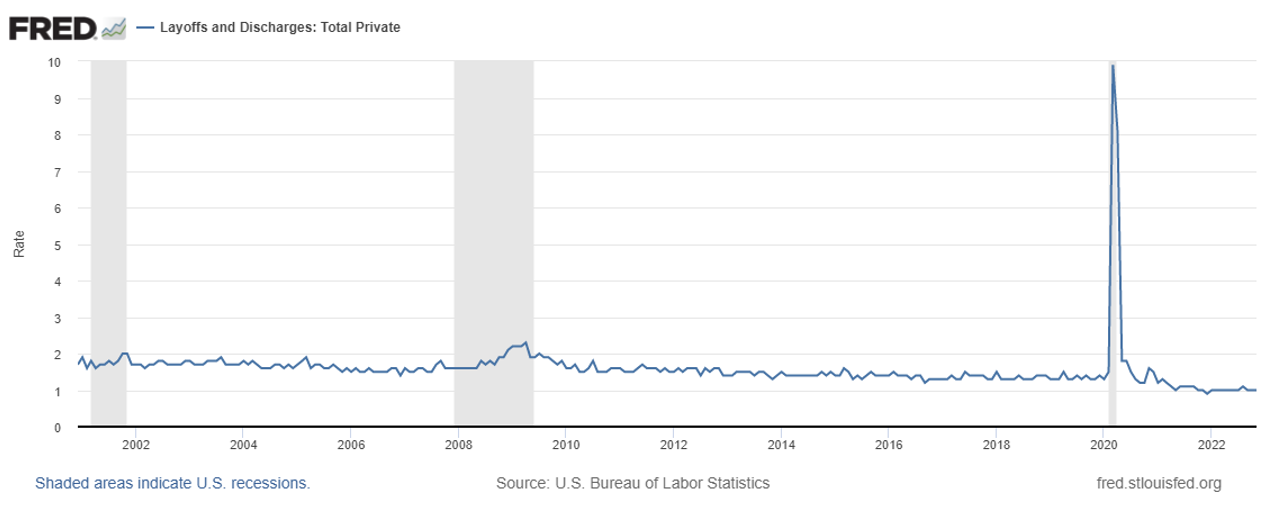

Job openings and quits as a fraction of employment are at historically high levels. The rate of layoffs plus dismissals continues to be at an historically low level. The media is focused on layoffs of some prominent firms (those make good human interest stories), but the overall rate of layoffs and dismissals is at an historical low. Cumulative net hiring during 2022 was 4.5 million workers—a large fraction of the labor force.2

Layoffs and Discharges as a fraction of total private employment3

Hiring is strong: in December, firms added 223,000 workers.4 Hiring was strong across almost all sectors. (Surprisingly construction was one of the sectors with net increases in employment; this may be due to the lagged effects of the infrastructure bill as well as onshoring initiatives.) The media accounts of the net additions having decreased are misleading. Clearly as the pool of potential workers (unemployed and discouraged workers) shrinks it becomes more difficult to gain new workers. At the extreme, new hires must converge toward zero.

Job openings as a percentage of employment were 6.4%, compared to a pre-pandemic peak of 4.7% in 2019.5 If we focus on the private sector the labor market is similarly strong, with job openings at 6.8% of total employment—well above their pre-pandemic peak of 5.1%—and layoffs plus dismissals well below pre-pandemic levels.6 Private sector layoffs and dismissals are 1.0% of total employment compared with 1.5% in February 2020.

All these indicators suggest that labor demand is very strong. We may expect some weakening in labor demand due to higher wages and changes in the composition of the labor force. Small businesses report that labor quality is their top operating problem (cited by 21% of small businesses).7 The San Francisco Fed has reported three consecutive quarterly declines in labor productivity. This is likely due to a combination of changes in the composition of the labor force and low productivity of newly hired workers as they learn their jobs and as other workers are reallocated to train the new hires. Despite the decline in labor productivity, firms are still reporting that they plan to increase employment.

To the extent that the high level of quits is due to falls in real wages and the use of signing bonuses to help fill job openings, we expect continued upward pressure on wages, after adjustments for changes in labor force composition.8 Wages growing faster than productivity will put pressure on the prices of services, other than rents. We are also seeing an increase in the demand for services. The increase in the share of employment in low wage industries such as leisure and hospitality will tend to depress reported average wages and thus give a misleading signal about wage inflation. A better measure of wage inflation is the wage data reported by the Atlanta Fed, which looks at wage changes for the same people and thus removes effects due to changes in the composition of the labor force. The Atlanta Fed is reporting median wage growth of 6.4%.9

Looking forward to the effects of higher interest rates on labor demand, the sectors that are most sensitive to interest rates are production of motor vehicles, residential construction and, to a lesser extent, production of other durable goods. Employment in manufacturing of motor vehicles and parts is less than seven-tenths of 1% of total employment.10 Employment in residential construction is less than six-tenths of 1% of total employment. Combined employment in residential construction plus motor vehicle and parts manufacturing is around 1.3% of total employment. This seems small in an economy with job openings greater than 6% of total employment. Durable goods manufacturing is roughly 5% of total non-farm employment. By comparison, in 1979 durable goods manufacturing was 13% of total employment. Thus, it seems unlikely that the contemplated increases in interest rates will be sufficient on their own to offset the strength of the labor market, bring down wages and dramatically increase unemployment.11

Labor Market Supply

If we consider the potential supply of workers, the most relevant measure is probably U-6, which is the percentage of the unemployed plus marginally attached workers plus workers who are working part time for economic reasons (can’t get a full-time job). In November U-6 was at an historical low relative to pre-pandemic levels (using data going back to 1994). The low level of U-6 suggests that there is not a sizable pool of currently available workers to fill the job openings. We find similar results using other measures of unemployment such as U-5, which measures discouraged workers (workers who are not looking for work but would like to get a job if one was available) plus unemployed workers currently looking for work, and U-3, which just measures the latter. The unemployment numbers came in at 3.5% for December, tied for an all-time low. Levels of discouraged workers and individuals working part time for economic reasons are also low by historical standards.

The 8.7% increase in Social Security payments starting in January combined with the incidence of long-haul COVID will likely keep labor force participation rates low. The persistence of COVID infections and the large increase in cases of flu and RSV will be reflected in decreases in hours worked as people stay home either because they are ill or need to take care of sick relatives. High job turnover can also impair growth in labor productivity.12 The decrease in effective labor supply (measured in terms of productivity) holding labor demand constant would be inflationary. Since demand appears to be increasing, the inflationary effects are stronger.

The prime age labor force participation rate (ages 25-54) at 82.4% is higher than it was between 2010 and 2019.13 The overall labor force participation rate at 62.3% is below its pre-pandemic levels and about where it was in 2016. This low participation rate is thus likely to be due to the aging of the labor force and the effects of COVID on labor force participation of older workers. Older workers do not appear to be being drawn out of retirement by the strong labor market. They can draw on increases in housing prices and Social Security benefits to finance retirement and may have changed their preferences in response to the risk of contracting COVID or to the effects of long-haul COVID.

Various measures of unemployment, including measures that include discouraged workers and workers that are employed part time for economic reasons, also indicate fairly low potential supply of workers. The increase in mortgage interest rates could further hinder discouraged workers from being available to employers in areas outside of commuting distance of the residence of the discouraged worker. While there is an increased amount of remote work, this is likely to be a small effect over the long run: in many cases work that can be done remotely in the U.S. can also be done more cheaply in low wage countries outside the U.S.

The takeaway is that I don’t think there is much potential for an immediate increase in the number of workers available to fill the large number of job openings.

In the short to medium term, the COVID pandemic seems likely to decrease labor supply both by increasing absenteeism and reducing labor force participation rates through the indirect effects of long COVID. An aging population in the developed world will divert workers toward caring for the elderly and away from supplying the goods and services measured in the Consumer Price Index (“CPI”).14

Turning to the likely path of long run labor productivity: the 2017 tax law calls for expenditures on research and development and on software development to be amortized over five years if pursued domestically and over 15 years for foreign spending. The tax law provided special benefits for real estate developers—especially those that utilized pass-through entities such as LLCs and limited partnerships. Diverting resources from research and development in order to free up funding to support the real estate industry is damaging to long run productivity and will contribute to inflation. Subsidies to the real estate industry distort the allocation of capital in ways that damage productivity. There are fewer if any positive externalities from construction of homes or other buildings, so diverting investment funds and skilled labor into the real estate industry implies less productivity-enhancing investment in industries with positive spillover effects on long run productivity.

The Penn Wharton Budget Model projects that skill-adjusted productivity will grow at an annual rate of 0.89% in 2020-2029 and will average 0.68% annual growth from 2020 through 2049.15 This is less than half the annual growth rate from 1980 to the present, and somewhat lower than the productivity growth rate of 1.06% from 2010-2019.

Balance Sheets

According to a recent Fed paper, households held about $1.7 trillion in excess savings as of mid 2022.16 Savings is defined as the difference between income net of taxes and consumption, and excess savings as the cumulative deviation from trend starting at the beginning of the pandemic.17 Most of the excess savings was held by the top half of the income distribution (roughly $1.35 trillion of the $1.7 trillion total excess savings). These individuals are experiencing relatively small increases in wages, but they can use their excess savings to support their consumption.

Aside from measured increases in savings, there have been very large increases in home values that can be drawn upon through home equity lines of credit (“HELOCs”), home equity loans or reverse mortgages. As opposed to stocks and bonds, home ownership is widely held and is the main source of personal assets. On the other hand, the same high interest rates that could cause a recession may deter people from borrowing against the value of their homes. However, the net effect of increased home equity is likely to provide a buffer against falls in demand.

On the business side, large U.S. firms account for a significant share of private sector employment and get most of their external financing through bonds. In aggregate, large firms have large cash balances, due in large part to the increase in earnings as a fraction of GDP.

On the other hand, a greater percentage of the liabilities of small- and medium-sized firms and foreign firms are floating rate bank loans and thus such firms are much more vulnerable to increases in interest rates. Large increases in interest rates may induce bankruptcies of small- and medium-sized firms, especially those that have only survived because of the availability of cheap credit. Overall, however, balance sheets seem strong; thus if we combine the cash positions of firms with their low-interest debt, large firms in the U.S. business sector seem insulated from the adverse effects of moderate increases in interest rates. The macroeconomic risk from higher interest rates lies in the risk of bankruptcies of small- and mid-sized firms. During the years since the global financial crisis default rates in the U.S. have been very low. That may be due to the low interest rates. In that case we may find default rates will exceed historical levels if interest rates stay at high levels.

Automatic Stabilizers

While I believe that the strength of the labor market and strong balance sheets have reduced the likelihood of a recession, recent changes in the tax code have reduced the effectiveness of automatic stabilizers: sources of revenue and expenditures that automatically dampen both booms and slumps by curtailing demand during booms and sustaining spending during slumps. Thus, if a recession were to occur it will be more severe than if the automatic stabilizers had been retained. The gradual eroding of automatic stabilizers due to recent changes in the tax code has perhaps received insufficient attention as a contributing factor to the severity of the Great Recession.

Note that while I’m illustrating the destabilizing effects of various programs, I’m not making a statement about the welfare implications. That depends on how one values the other benefits and costs of the programs.

The 2017 tax bill seriously impaired the effectiveness of automatic stabilizers in the tax code, thus increasing the risk of serious recession. On the other hand, the expansion of Medicaid benefits and the increased spending on Medicare and Social Security provide a measure of spending that is independent of other economic conditions.

Corporate profits are highly pro-cyclical. The 2017 changes to corporate tax law eliminated back averaging, which transfers funds to corporations that are incurring losses during a recession. These changes also increased forward averaging. Back averaging gives money to firms that are suffering losses after previously earning profits; this is more likely to occur during recessions. Forward averaging gives money to firms that had previously incurred losses; this is most likely to occur during a boom that follows a recession. Thus, back averaging smooths the business cycle and forward averaging exacerbates it. These two measures, combined with the cut in corporate tax rates, increase the magnitude of the pro-cyclicality of after-tax corporate profits and thus increase the volatility of the business cycle. Other revisions disallowed deductibility of interest payments above 30% of EBIT (earnings before net interest expense and taxes).18 Firms that incurred losses can owe taxes. This is most likely to happen during a recession that is accompanied by high interest rates: the recession would depress operating profits, which reduces the tax deductibility of high interest rates, and the combined effects of lower operating profits and higher interest rates could cause the firm to incur losses while still owing taxes. Because tax obligations have priority in bankruptcy over other debts incurred prior to bankruptcy, those firms may have particular difficulty getting financing to avoid bankruptcy. Thus far we haven’t seen this provision of the tax code leading to less use of debt financing over equity financing. Holding leverage fixed, it is an automatic destabilizer.

Entitlement programs are somewhat counter-cyclical and can support the economy during a downturn. More people qualify for Medicaid and other means-tested programs during a slump. Spending on Medicare and Social Security and other government funded retirement programs does not fall during recessions and thus helps sustain aggregate demand.

The long-term effects of underfunded entitlement programs and cuts in revenue from indexing tax brackets and cutting tax rates are problematic, but it is difficult to know when the impact of the resulting cumulative deficits will impact the economy.

Fiscal Policy: Spending Increases

While U.S. deficits will shrink from the extraordinarily high levels during the COVID pandemic, they will continue to be very high. Due to the 8.7% increase in CPI-W inflation from September 2021 to September 2022, Social Security, disability payments and SNAP benefits will increase by 8.7% starting in January. Income tax brackets will also be adjusted by 8.7%.

The 2022 appropriations bill will increase defense spending by roughly 10%. It is unclear when the increased appropriations for weapons will be spent, but the increases in salaries will have an immediate impact on demand. Increased employment in the defense industry will decrease labor supply in other sectors that contribute to the components of the CPI and thus will be inflationary. Increased demand for capital equipment will similarly decrease the capital available in other sectors, suppressing supply and thus increasing prices. There are some differences of opinion on the magnitude of the increase in non-defense spending in the budget bill, but it seems roughly in line with inflation and perhaps to be a decreasing share of GDP. The Medicare and Social Security deficits will almost surely increase, as will interest on the national debt.

Balance of Trade and Exchange Rate

The appreciation of the dollar against other currencies has led to a large cumulative increase in imports of foreign goods. Imports of goods increased by roughly 42% from 2020 to 2022.19 Thus we have exported much of the inflationary effects of the stimulus package. A large percentage of U.S. purchases of motor vehicles and parts and other goods is imported. The prices of those goods have recently been falling, due in part to the appreciation of the dollar—a strong dollar means that the cost in dollars of producing abroad falls, which enables foreign producers to sell at lower prices. This fall in the price of imports is a one-time shot and is not likely to continue.

Housing

Housing merits special attention. Shelter is roughly 1/3 of the CPI, and peculiarities in how the cost of shelter is calculated affect reported levels of inflation. These peculiarities affect the CPI and to a lesser extent PCE Price Index but do not affect the likelihood of recession, except insofar as the reported inflation numbers affect cost-of-living adjustments, sentiment and policy decisions. Therefore, I’ve relegated the treatment of housing to an appendix.

Sentiment

The biggest risk to the U.S. economy is negative sentiment. If decision makers interpret a negative yield curve as a precursor of a recession, then they will retrench and a recession will occur. This is a psychological phenomenon but it is nevertheless very real. Falls in spending and falls in investment generated by a fear of a recession will cause a recession.

Although surveys show high levels of pessimism, behavior is different. Firms continue to hire at high rates. As mentioned previously, in December the private sector added 223,000 jobs, around twice pre-pandemic levels. The media writes stories about the tech firms that are laying off workers; it doesn’t write stories about the firms retaining workers that under other circumstances would have lost their jobs, or about the many firms that are adding workers. Good news doesn’t sell.

While spending on consumption goods has fallen, this may be largely due to falls in prices of imports and the switch from spending on goods to spending on services. The GDPNow data from the Atlanta Fed is forecasting a 4.1% increase in real GDP in the fourth quarter of 2022.20 Again, these data are inconsistent with retrenchment by firms or consumers as would be happening if they believed a recession was imminent.

Efficacy of Federal Reserve Policy

The last time the Fed had to intervene to combat high inflation was in the late 1970s and early 1980s, causing the federal funds rate to peak at 19% in 1981.21 The methodology used to calculate the cost of owner-occupied housing changed in 1983. If we used the pre-1983 methodology today or computed inflation in the early 1980s using the current methodology, we would find inflation is currently closer to the levels of the 1980s than would be apparent from the reported numbers. Prior to 1983 there were restrictions on the interest rates that banks could charge on checking accounts and time deposits. Thus the high interest rates paid on treasury securities caused a massive flight of deposits out of the banking system. This effect is no longer present: banks can respond with higher interest rates on deposits to avoid capital flight. Also, the banks have large cash balances and can use their holdings of government securities to access cash from the Federal Reserve. Because of the long maturity of firm bond debt and strong balance sheets, large firms are less affected by higher interest rates than at most times in the past.

In the short to medium term, higher interest rates have the most immediate effect on demand for motor vehicles and housing. Inventories are low and employment in those industries is not a very significant fraction of total employment. High interest rates also depress investment by firms, but there are strong tax incentives to invest in new plants and equipment, as well as trade tensions that are encouraging firms to engage in more onshoring. The increase in defense and infrastructure spending also will be stimulating private investment.

The main tool that the Federal Reserve has to cause disinflation is forward guidance: these communications affect mass psychology and thus behavior. If the Fed communicates its intention to fight inflation, and decision makers believe that other decision makers will retrench in response to these communications, then the economy will contract and there will be disinflation. Economies have multiple equilibria and communications from the Fed and commentators can affect sentiment in ways that have real effects on the economy.

Concluding Remarks

My forecasts are based on economic fundamentals. I have no expertise in predicting changes in sentiment. In particular, forecasts of recession could cause a recession. So even if the forecasts are based on a misunderstanding of the economic fundamentals, those forecasts could end up being self-fulfilling because they are widely believed. Forecasts of recession could also cause firms to be cautious about wage increases and workers to be reluctant to change jobs and give up seniority which can be valuable in the event of layoffs. Consequently, inflation could be below the rates we’d expect from the economic fundamentals. Because my analysis is solely based on economic fundamentals and ignores these important psychological feedback effects and other factors affecting sentiment, the predictions in this commentary should be taken with due caution.

Based on fundamentals, I think a recession is highly unlikely unless the Federal Reserve decides to raise interest rates to well above the forecasted levels. CPI Inflation is likely to subside in the next few months but then re-emerge. Prices of services respond more slowly to changes in demand than do prices of goods, so as people switch from purchases of goods to purchases of services, and as the fall in commodity prices and the strength of the dollar are reflected in the price of goods (especially imports, gasoline and food), the fall in prices of goods will show up in lower inflation rates in the near term. At the same time, the supply of rental housing that is coming on the market will depress prices of new leases and will depress the imputed rental value of owner-occupied housing as well as of rentals. The decrease in life expectancy of people over 65 that started with the pandemic will decrease spending by retirees and may have a slight disinflationary effect, which could offset the lower employment levels that have accompanied the pandemic. The decline in residential construction, sales of existing homes and sales of new cars will also dampen inflationary pressures.

These disinflationary effects will be countered by the 8.7% increase in Social Security benefits and other inflation-linked entitlements and the changes in tax brackets starting in January. The strong labor market will continue putting pressure on wages. Mandated increases in salaries in the defense department and the lagged effects on spending of the infrastructure bill will also increase aggregate demand. The net effects are likely to cause inflation rates to fall in the near future but for CPI inflation to remain well above the 2% target set by the Federal Reserve. I expect unemployment to remain below the 4.5% level that seems to be the consensus regarding the “natural rate” (non-cyclical rate) of unemployment. (While I’m somewhat dubious about this number being the natural rate, it may be a driving factor for the Fed’s interest rate policy.) Therefore, I think a cut in interest rates is unlikely over the next 12 months.

Starting sometime in late 2023 or 2024, the inflationary effects of government initiatives will be felt more strongly. These inflationary government initiatives include both direct spending and multiplier effects of subsidies for investments, as well as regulatory rules that induce more investment. Mandated spending on long-term infrastructure projects will continue to influence demand for construction work as the projects work their way through the permitting and approval process. Contracts for defense procurement goods will have similar long run effects.

Spending on defense decreases the supply of labor and capital available for the goods and services included in the CPI. By contrast, spending on roads also decreases labor and capital available for other activities, but spending on roads also increases labor productivity—largely by improving the allocation of labor. There is also likely to be increased spending by state and local governments to fill the need for teachers, medical personnel, police officers and other civil servants. Employment by state and local governments will reduce the supply of labor available for sectors supplying the goods and services measured in the CPI and thus could have a long-term inflationary effect. The other factor affecting labor supply is long-haul COVID, and recurrence of new variants of COVID will continue to depress labor supply. Overall, these trends seem likely to lead to persistence of inflation. For the reasons described above I see very little prospect of a recession at current interest rates or even ones marginally higher. Thus I see little prospect of the Federal Reserve goal of 2% inflation being achieved in the next few years. The recent fall in oil prices and natural gas prices and the fall in the stock market will likely cause CPI inflation to moderate over the next few months. But the tailwinds from a tight labor market and government spending will prevent the Fed from getting inflation down to its goal of 2% in the next few months unless it is willing to push interest rates high enough to cause a recession. In particular, I believe that inflation over the next five years will be above the 2.3% rate implied by the market for inflation swaps.

In the very long term, the exponentially growing ratio of debt to GDP is a potential disaster. I doubt this issue will be addressed before the Medicare trust fund runs out of money and probably not until the Social Security trust fund runs out of money, which is currently expected to happen in 2034. If nothing is done before then, there could be an economic crisis if investors lose confidence in the fiscal stability of the U.S. In the words of Herbert Stein, “if something can’t go on forever, it won’t.”

A wild card is the deal that Kevin McCarthy made to become speaker. If he will hold the increase in the debt ceiling hostage to cuts in spending then we are entering uncharted territory. It is possible that a deal will be reached that addresses the foregoing long run fiscal imbalances, or gives the appearance of doing so without effecting fundamental reforms; it is also possible, albeit unlikely, that the U.S. defaults on its debt.

Two caveats to the analysis: low inflation rates in Japan both in absolute terms and more recently relative to other countries, and the relatively low PPI inflation rates. Relatively low inflation in Japan in the face of large fiscal and monetary stimulus, as well as an aging population, are a challenge to standard economic analysis. The PPI inflation rates, which measure the prices that domestic producers of goods and services are charging, are significantly lower than the inflation rates in either the CPI or the PCE. This could be due to low response from firms—the firms which are raising prices the most may be less likely to reply to the survey—as well as the omission of services such as the implicit rent on owner-occupied housing that are not included in the PPI. On the other hand, it is possible that the PPI is capturing features of the economy that are missed by other inflation measures. As always, a measure of humility is always useful in forecasting. As Niels Bohr said, “Prediction is very difficult, especially about the future.”

Appendix

The rental component of the CPI is average rent, and it thus lags behind market conditions which affect the rents on new leases. The rents on new leases have been falling recently, but still are greater than average rents, which we estimate will generate artificial price increases on rents as leases turn over. The other distortion comes from the imputed rent on owner-occupied housing which is roughly 24% of the CPI-U (the measure of CPI reported in the media). Since the owners are implicitly paying this rent to themselves, monthly or annual changes in the imputed rent of owner-occupied housing does not cause significant changes in the cost of living, and thus, while changes in prices of utilities or property taxes affect discretionary income available for other goods and services, changes in the imputed rent on owner-occupied housing do not directly affect spending for other goods and services,22 aside from perhaps the indirect and opposite effect of higher imputed rent increasing the value of housing and thus increasing potential spending by homeowners.23

Another distorting effect comes from the fact that while around 90% of owner-occupied housing is single-family homes, there is relatively little rental of single-family homes. Consequently, the formula for imputing the rent on owner-occupied dwellings places only 33% weight on the data from rents of single-family detached dwellings. While total starts on residential construction are falling, starts on multi-unit dwellings are holding up well and starts on units that are intended to be rented are increasing strongly. As of November, privately owned housing units under construction is up 14.5% from a year ago; this is mainly driven by a 26.2% increase in five or more unit dwellings. Thus, in the short run, I would expect the increase in the supply of rental units to suppress pressure on rents and to perhaps cause a fall in the rents on new leases. On the other hand total starts are down 16.4%, while total starts of multifamily units are up 24.5%.24 Thus in the long run the shortfall in total supply of residential units and the lack of affordability of home ownership due to higher mortgage rates and higher home prices is likely to cause rents on apartments and attached homes to rise, thus leading to price inflation in the shelter components of the CPI.

As a result, the peculiarities of how owner-occupied housing is treated in the CPI seem likely to depress CPI inflation in the short run, but may increase it in the long run as the decrease in the supply of new residential units causes rents to catch up with the cost of home ownership. The intermediate term effects on measured CPI inflation are ambiguous—an increase in multi-family starts might cause average rents to decline even as housing shortages increase.

Disclaimers:

This commentary has been prepared by Dr. Andrew Weiss and reflects the opinions of Dr. Weiss. This is not an offer to sell, nor a solicitation of an offer to buy any security of any fund (a “Fund”) managed by Weiss Asset Management LP or its affiliates (“WAM”) or any other investment product or strategy. Offers to sell or solicitations to invest in a Fund are made only by means of a confidential offering memorandum and in accordance with applicable securities laws. An investment in a Fund involves a high degree of risk and is suitable only for sophisticated investors that are qualified to invest therein. Commodity trading involves a substantial risk of loss.

This commentary may not be reproduced or further distributed without the written permission of Dr. Weiss. This material has been prepared from original sources and data believed to be reliable. However, no representations are made as to the accuracy or completeness thereof.

Although not generally stated throughout, this commentary reflects the opinion of Dr. Weiss, which opinion is subject to change and neither Dr. Weiss nor WAM shall have any obligation to inform you of any such changes.

This commentary includes forward-looking statements, including projections of future economic conditions. Neither Dr. Weiss nor WAM makes any representation, warranty, guaranty or other assurance whatsoever that any of such forward-looking statements will prove to be accurate. There is a substantial likelihood that at least some, if not all, of the forward-looking statements included in this commentary will prove to be inaccurate, possibly to a significant degree.